James Douglas and the Capture of Roxburghe Castle

Edward I of England, known as ‘Longshanks’ due to his height, was a warmongering sort who was not content to merely sit the English throne.

Edward craved influence in the rest of Britain and beyond, so a large proportion of his time was spent at war with his neighbours in Wales, Ireland, France and Scotland. Despite the large number of castles he built in Wales, it is perhaps his exploits in the north that earned the most notoriety, and caused him to be known to posterity as Scottorum Malleus, ‘the Hammer of the Scots’.

Edward was succeeded by his son and namesake, yet Edward II was no match for Longshank’s formidable reputation. He inherited his father’s dominions and a fractious nobility that he struggled to control. The gains previously made north of the border were slowly eroded by a Scotland resurgent under the stewardship of King Robert Bruce.

Whilst he refused to meet the English in open battle, Bruce had a great deal of success by keeping his forces small and mobile, by hiding and ambushing the English, always keeping them wrong footed. This even caused the frustrated King Edward to write to the Pope, complaining that his efforts to quell rebellion in Scotland were thwarted by such underhanded tactics, with his commanders often finding that the Scots had ‘concealed themselves in secret places after the manner of foxes’.

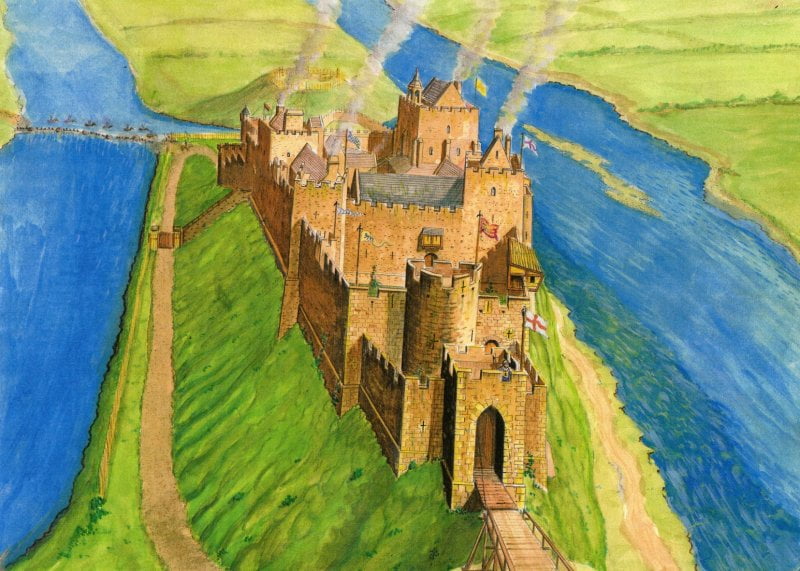

By 1314, Bruce had succeeded in re-taking most of the Scottish castles previously held by the English, and his forces were able to raid into England itself. One bastion that still held out against the Scots was Roxburgh castle, a large border fortress naturally moated by the twin rivers of the Tweed and the Teviot, in an important strategic position with links to Berwick upon Tweed and the North Sea beyond. Edward’s response to the growing Scottish threat was to muster his forces and begin to plan a significant invasion of Scotland in a bid to regain what had been lost.

Early in 1314, Edward Bruce, King Robert’s brother, laid siege to Stirling castle. Its English commander, Philip Mowbray, agreed to surrender this key stronghold unless relieved by an English army before June 24 th . As the English king planned his response, James Douglas, known to many as the Black Douglas, a great friend of King Robert, was dispatched to re-take the border fortress of Roxburgh for the Scottish cause. It was at Roxburgh that King Robert’s sister, Mary Bruce, had been taken and placed in a cage exposed to public view on the orders of Edward I. Roxburgh was a symbolic as well as a strategic prize.

The Scots had ever struggled to subdue the larger castles held by the English. They lacked the heavy equipment and weaponry that would have been used to breach the massive walls and penetrate the stout gates and keeps that protected the English garrisons. If Douglas was to take Roxburgh, he would have to do so through cunning, rather than by direct assault. In the chill of mid-February, Douglas put his mind to how this may be done. The gates were too heavy to be broken down, and the walls were high. The view from the parapet was good, especially on clear nights, when a man on the walls could see for miles in all directions. This meant that a party of men looking to assault the walls would be easily seen on their journey to the walls. Surprising the English garrison looked to be impossible. As Douglas examined the fields around the castle, a plan began to form…

On the night of 19th February, Shrove Tuesday into Ash Wednesday, Douglas put his plan into action. He ordered sixty of his best men to dress in voluminous dark cloaks and animal skins, to approach the walls in a slow and haphazard manner. Some of the men carried grappling hooks with slatted rope ladders attached, all hidden beneath their cloaks. Prior to Lent, Douglas had gambled that the garrison may well be enjoying a dram or two to see them through the cold February night. As he and his men crawled slowly toward the castle on their hands and knees, it seems his plan was working. To any watcher on the walls, the Scots would appear to be cows, moving slowly across the fields, just like the ones Douglas had observed in the days leading up to the attack. Once at the castle walls, Douglas’ men threw off their cloaks and cow-hides, and used the rope ladders to scale the walls, clearly doing so quickly enough to avoid detection.

One version of the tale has a woman sat on the battlements (it is unclear as to why she should be doing so in the middle of the night in February!) with her young baby, singing it to sleep with the song, ‘Hush ye, hush ye, The Black Douglas will not get ye.’ Should this unlikely scenario be true, imagine her surprise at being confronted with none other than the Black Douglas himself, rising up over the parapet in front of her. In this version of the tale, Douglas ensures the woman is unharmed and safe as the fortress falls to his men. In other accounts, it is Douglas’ second in command, and the man responsible for the construction of the ladders, Sim Leadhouse, who was the first man over, and he threw the first Englishman he found screaming from the top of the wall to the ground far below.

Douglas’ men the quickly made their way to the gatehouse, where the opened the castle gates for the main body of Scots to flow in. The alarm was raised, and the Gascon governor and his men retreated to the main Donjeon tower where they stood on the high battlements and hurled insults at the Black Douglas. The insults stopped when the governor allegedly received an arrow in one cheek which passed through his mouth and out through the other side. With the arrow shaft gripped between his teeth, the governor found it much harder to shout insults, and quickly agreed to surrender the castle to Douglas and his men.

By the time the massed hosts of England and Scotland met on the field of Bannockburn, a battle that ended in terrible defeat for the English, Roxburgh castle was back in Scottish hands, not through sheer force of arms, but through a cleverness that characterised Scottish tactics throughout this period. Victory seemingly sometimes goes to those who are cunning, like a fox, yet dress like a cow. A lesson to us all.